June 28th, 2013 § § permalink

The transformation of the global waste stream into mostly stuff made of single-life plastic was presaged in the 1930s with the invention of polyethylene (your plastic bottle), and then kicked into overdrive in the 1960 when the stuff became cheap to make. Since then, human impacts have ushered in an new ecological niche called the plastisphere.

Plastisphere /ˈpla sti sfi(ə)r/ an abundant substrate of anthropogenic origin in the marine environment that is receiving increased attention. (Amaral-Zettler, L. A.; Zettler, E. R.; Mincer, T. J.)

This is a more descriptive name IMHO than the garbage patch, trash vortex, etc., which effectively conjure images of great rafts of chunky landfill debris. Surely, big plastic is a devastating issue for marine ecosystems, evoking heartwrenching images of “ghost nets” that break free from commercial fisheries, plastic trash on the outskirst of the deep sea floor, and the ubiquitous bird belly full of plastic caps. Consider this the “charismatic macrofauna” of the plastisphere.

But wait, there’s more.

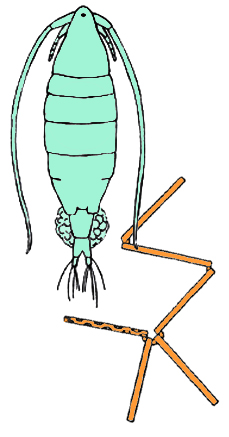

Most ocean plastic is small, like plankton. It is there in large amounts mixed in with the foundational slurry of the food web. And now researchers are following natural selection as it plays out in this tiny-yet-vast realm of the plastisphere.

As it turns out, while plastic “eats” our oceans, something eats the plastic.

From

For about four decades, it’s been known that plastic is collecting in the open ocean. Now, scientists have found this debris harbors unique communities of microbes, and the tiny residents of this so-called plastisphere may help break down the marine garbage.

Inhabitants of the plastisphere include members of a group of bacteria, the vibrios, known to cause disease, and microbes known to break down the hydrocarbon bonds within plastics, genetic analysis revealed. But most important, the communities of microbes on the plastic pieces were quite different from those found in samples of surrounding seawater.

“It’s not a piece of fly paper out there with things just sticking to it randomly,” said study researcher Tracy Mincer, an associate scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, referring to the plastic. “There are specific groups of microbes that are attracted to that environment and are adhering to it and living on it.” -Wynne Parry

June 23rd, 2013 § § permalink

Last week I took a field trip to the Dutch Kills tributary of Newtown Creek with Drs. Michael Levandowsky and Sarah Durand to sample plankton. Sarah is a fixture on Dutch Kills, and is currently enjoying her sabbatical from LaGuardia Community College (although sabbaticals do tend to become as full of responsibility as ever, I am learning), located steps from the infamous Superfund site. She and her colleague Dr. Holly Porter-Morgan, the director of the environmental science program at LaGuardia, have regularly brought their classes out to sample water and benthos on the creek, and are the resident scientists of Newtown Creek. Michael I have introduced already.

Finding a time for all three of us to get together on my favorite underdog waterbody was something I had been looking forward to for awhile.

Michael on plankton and Sarah on dissolved oxygen.

Despite popular opinion, Newtown Creek is alive. I would never use adjectives such as “clean”, “pathogen-free” or “high-functioning”, but I can state with some authority that Newtown Creek is surprizingly alive. The ecosystem that exists today in the backyard of the Industrial Revolution is what one might call “impaired”, hamstrung by historic contamination and persistent sewer overflows, but it limps along (and occasionally leaps!) nonetheless.

Dutch Kills has always been fascinating to me, as it lies on a transitional borderline between the relatively good water quality at the mouth of Newtown Creek, and the “heart of darkness” further up. There is a large CSO that functions as the headwaters, and the entire tributary might suddenly turn a milky mint green, precipitate gloopy green algae blobs, and then turn a tea-like red the next day. She moves in mysterious ways.

Sarah hosted our dip, and allowed us to take a preliminary look at our findings back at the lab. We used two different tows, one of coarser and one of finer mesh. This is what we saw in the coarser mesh:

Clockwise from top left: Possibly a freshwater alga, a barnacle larva, something of botanical origin that stumped us, and a skeletonema.

Michael made off with an aliquot of the fine mesh sample and reported… “I looked at the sample from the 10 um tow and it’s rich in phytoplankton. Skeletonema dominates, but there are also dinoflagellates, and much else.”

More will be revealed!

June 20th, 2013 § § permalink

Some of my interest in plankton has to do with the fact that I am in a nomadic, “wanderly” chapter of my life this summer. Having been firmly rooted in NYC for over 13 years, an auspicious enough number I guess, a combination of desire and need pushed me into a sabbatical from The City to tend to personal and family affairs. I cycle regularly between Pittsburgh, PA, the place of my ancestors, New Bedford, MA, the place of my boat/boyfriend, and NYC, the place of my career.

I am very grateful to have supportive family, friends and colleagues in each of these places, who push me forward when I get stuck, transfusing the chutzpah one needs to extract oneself from a quagmire.

One thing that has happened during this uprooting is that I have returned to photography as my main form of record keeping. Another thing that has happened is that my obsession with family history has transitioned from a late night, internet-based exercise in database management to a face-to-face, you-talk-ill-write, field expedition.

This week my Mom and I went to visit the Marshall County Court House in Moundsville, West Virgina, looking for family history. It is an area that has experienced a massive boom in oil and gas extraction (aka. the Ohio Valley Boom, but I prefer the term Frack Attack!), and there have been rumors of mineral rights in them thar hills, where the early Irish immigrants on my mom’s side came and farmed taters in the West Virginia wilds in the mid 1800s.

It was a long, stream-of-consciousness sort of day, where we got sidelined many times by little breadcrumbs of family history that led to unexpected places. We ended up meeting distant relations we didn’t know existed, visiting mysterious gravesites on our old farm, stumbling across a barn build by my teenage Great Grandfather, and tasting the fetid well water that results from decades of coal, oil and gas exploitation.

Old kin and modern residents of our “home place”.

The Grave of the Unknown Priest, complete with gaelic cross carved by an Italian inmate of Moundsville Penitentiary.

Barn built by Philip Henry Markey circa 1878.

We did not come home gas barons (um…good?), but our ramble revealed our family’s fingerprints are still all over Marshall County, West Virginia. Moreover, we turned up a restaurant that serves a fine fried baloney sandwich, if you are ever hungry in the Ohio River valley.